This region starts at the western end of Longis Bay and includes the Nunnery and the sandstone overlay all along the S. cliffs to Bluestone Bay and L'Etac de la Quoire and the area of mainly agricultural land of La Grande Blaye, between the coast and the Longis Road, from the Nunnery to its junction with Valongis.

Longis Bay, shallow and sandy, well sheltered and with a narrow entrance, was almost certainly the island's earliest harbour. In direct view from the French coast at Cap de la Hague 9 miles away across Le Raz Blanchard (The Race) it would have been the obvious point for early settlers in the Stone, Bronze and Iron ages to land. The sea level was much lower than today then and they would have touched land below today's extreme LWM. The flat sandy bottom of the middle of the bay is an ideal spot for beaching flat-bottomed boats, which almost certainly led the Romans to use it as their base and build the original fort at the Nunnery up to 100m or so inland, just where a good stream of fresh water runs out onto the shore. The height of Essex hill commanding the whole bay area would have been an excellent lookout position and, in later times a watch tower was present here, long before Les Murs de Haut, started in the reign of Henry VIII and now known as Essex Castle, was built.

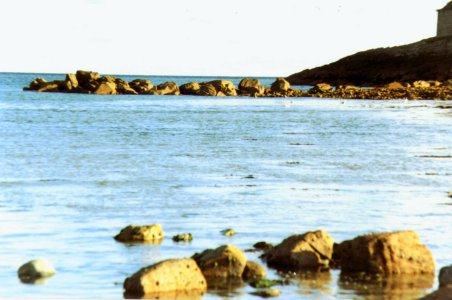

Soon after his restoration in 1660, Charles II ordered the building of a stone jetty on this side of the bay, the remains of which can still be readily seen as the tide falls, projecting nearly half way across this part of the bay, (Figure 74, below). Archaeological finds during the last 170 years, with tools, weapons and domestic utensils, going back some 4,000 years, indicate that Longis Common certainly held the earliest settlement on the island and the bay remained the principal harbour until the stone jetty was built at Braye Bay in 1736.

After the sudden rise from the flat E and NE coastal areas to the top of Essex Hill the land then continues at an elevation of around 85-90m to the western end of the island. As will be seen from the geological map on page 2, the underlying diorite or granodiorite of the central part of Alderney is overlain on the coastal side of this whole 'region' with a layer of sandstone, in places up to 120m thick, faulted at about 45º. Alderney is the only Channel Island with any sandstone in its geological formation. An area of the central part of the island has a loess overlay of windblown soil and the whole of the high level part of the island forms the agricultural region knows as La Grande Blaye, the 'greater corn-growing land', to distinguish it from Les Petites Blayes, along the western coast. (Figure 75. Trough at Vau Renier).

Divided from the rough cliff area of former Crown or common land, later distributed amongst the people by the Crown in 1830, this agricultural area is surrounded by an earth and stone bank surmounted by gorse and bramble to keep cattle out, known as La Costière. There are a number of cattle watering places along its length placed where springs produce a year round flow of water. The troughs, gulleys and cobbled standings which can be seen today at some of these, were probably constructed in Victorian times and the cattle, tethered whilst they grazed were then taken to them for water twice a day. The bracken from the common lands was cut for bedding and the gorse cut and dried regularly, to fuel the bread ovens present in most farmhouses at that time.

Divided from the rough cliff area of former Crown or common land, later distributed amongst the people by the Crown in 1830, this agricultural area is surrounded by an earth and stone bank surmounted by gorse and bramble to keep cattle out, known as La Costière. There are a number of cattle watering places along its length placed where springs produce a year round flow of water. The troughs, gulleys and cobbled standings which can be seen today at some of these, were probably constructed in Victorian times and the cattle, tethered whilst they grazed were then taken to them for water twice a day. The bracken from the common lands was cut for bedding and the gorse cut and dried regularly, to fuel the bread ovens present in most farmhouses at that time.

Agriculture was carried on in a communal strip system, which was not changed during the periods of land enclosure from the 16-18th centuries, carried out in Britain and the larger Channel Islands. It was governed by strict laws and customs for planting, harvesting, turning the cattle in in winter to graze the stubble and maintaining it weed free. The light mainly sandy soil was heavily manured for centuries by vraic (seaweed), brought up from the shores in spring and autumn, with another set of well established customs strictly kept for its gathering. This maintained fertility and helped retain soil moisture and, as far as can be ascertained, corn crops were grown continuously, with little fallowing. Potato growing was introduced in the late 18th century and some of the customs were modified to suit the later maturing of this crop. These laws and customs were kept until the island was evacuated in 1940 when a considerable proportion of the islanders were still engaged in agricultural activity, mostly with small holdings, each farmer keeping a cow and a few pigs or sheep and growing much of the food their families consumed, many of them also working in the stone quarries for their main employment. Even today there are few dividing walls or fences across the area.

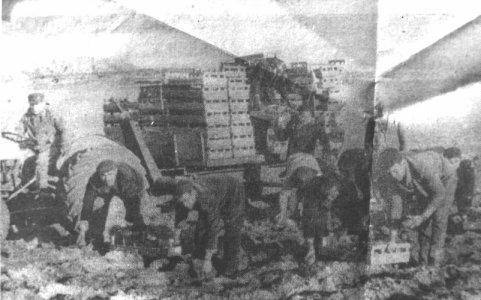

......................................................As has already been mentioned under Region 2, when the islanders began to return in late 1945, the island was run as a communal farm for almost two years, (Figures 76/77 either side). The subsequent horticultural enterprise kept many people employed and resulted in pickers being brought in from UK to help with the flower and potato harvests. Italian workers were imported and housed in Fort Tourgis in the late 1950s - early 60s. Many married island girls and their descendants are still here. Transport di

fficulties saw the decline of crop exports, as the rising costs made them uncompetitive and, with the introduction of many, often wealthier, British settlers, from UK and the former colonies, attitudes to education standards; which were gradually brought up to UK levels; and to a

fficulties saw the decline of crop exports, as the rising costs made them uncompetitive and, with the introduction of many, often wealthier, British settlers, from UK and the former colonies, attitudes to education standards; which were gradually brought up to UK levels; and to a

Figure 78 (abvove). Daffodils growing on Les Petites Blayes, about 1950

preference for better paid, cleaner, less physically demanding work, by the better educated youngsters; agriculture declined until with the death of the last dairy farmer in 1999 it virtually ceased.

.Figure 79. Italian workers harvesting potatoes

.....c. 1960 (from an old newspaper cutting).......

The farm house and some of the land had been rented, but the farm and those agricultural buildings on its land, were later bought by a local landowner and, in May 2000 a tenant was found for the property, who proposed to carry out the planning consent already given to the previous owner and build a new Dairy, the building and equipment of the old States Dairy now being unfit for continued use. Although two of the pedigree bulls and some of the milk cows had been slaughtered when no buyers could be found, there were still apparently about 110 cows and calves on the island and the new tenant hoped to be able to restart the production of Alderney milk as soon as a new dairy was built and equipped to conform with current hygiene standards.

The farm house and some of the land had been rented, but the farm and those agricultural buildings on its land, were later bought by a local landowner and, in May 2000 a tenant was found for the property, who proposed to carry out the planning consent already given to the previous owner and build a new Dairy, the building and equipment of the old States Dairy now being unfit for continued use. Although two of the pedigree bulls and some of the milk cows had been slaughtered when no buyers could be found, there were still apparently about 110 cows and calves on the island and the new tenant hoped to be able to restart the production of Alderney milk as soon as a new dairy was built and equipped to conform with current hygiene standards.

By September 2000 a good start had been made on cutting fields for hay and silage and mowing and clearing Ragwort from other fields. He also proposed to extend crop production beyond the necessities of the animals. Now in 2005 the dairy farm is well established and keeps Alderney supplied with clean fresh full-cream, semi-skimmed and skimmed milk, some cream, ice cream and yoghurt, when there is a surplus of milk and small quantities of excellent, well hung, beef, lamb and pork, both direct from the farm, or butchered, packed and chilled, from the local grocery shops. The land all round is in much better heart and a new modern dairy and a farmhouse have been built on the site, making it a considerable asset to the island.

This has given a new lease of life to agriculture in Alderney and help to prevent further succession to scrub of at least some part of the Blayes.

.

Many vergées of the land in the Green Belt, (see Appendix on legislation), particularly on the cliffs, now belong to non-resident families, whose parents or grand parents had emigrated to the colonies during hard times here and have inherited it from their islander relations, but have no interest in looking after it. The States too seem never to have enough agricultural team workers to attempt to keep their own land clean. As a consequence, over the last 30-40 years; gorse, bracken and bramble scrub has gradually encroached on much of cliff areas and of some of the agricultural land.

Changing living standards, with more women going out to work and thus having less time and energy for domestic chores, has resulted in a huge upsurge in the use of ready-prepared 'convenience foods'. There is now no mill to grind flour for bread making and comparatively few households still make their own bread. Thus, hardly any corn has been grown for years, except barley and oats for animal feed; few potatoes and no carrots are now grown, due partly to the importation of ready packed, clean-washed produce in convenient small bags by the food shops; and partly to the lack of workers willing to harvest them.

Since the introduction of myxomatosis, few local rabbits, once a staple meat dish for many families, are now eaten and, when their numbers increase again, they are more often excessively controlled by poisoning or gassing. The development of silage harvesting, whilst there were still enough cattle and sheep on the island to need large quantities of winter fodder, has meant that traditional hay-making, both preceded and followed by grazing, and other traditional farming techniques, have been dropped. As a consequence meadows have recently been mown for silage several times in the season, the wild flowers in them have not had time to flower or set seed and have slowly disappeared. The lack of enforcement of the Mauvaises Herbes laws has allowed Ragwort, Docks, 'Stinking Onions' and Hogweed in particular, to spread greatly, all now having reached the point where it would be almost impossible to control them. In 2003/4, to save the States embarrassment, as much of the infestation was on public land this law was finally reduced to Ragwort only.

All these factors are signs of modern 'progress' but have had a considerable, often adverse, effect on the landscape and ecology of the island. With fewer rabbits and almost no sheep, short turf habitats are vanishing and with them the minute plant and animal species which need this type of habitat.

A new, suburban, obsession with "tidiness", introduced in the last five years or so by recent settlers, has resulted in pressure on the States for commons, traditionally grazed and cut for hay twice a year, now being mown every few weeks and farm animals are excluded from them for "sanitary" reasons. Verges are mown with a depressing frequency and in both cases, the finely chewed up cuttings left to rot on the surface, resulting in the complete suppression of the smaller wildflowers and the subsequent nutrient enrichment of the soil, which creates an unacceptable environment for many "poor soil" species. The loss of some of these has resulted in a considerable reduction of butterfly, moth and other insect species numbers and spraying hedge bottoms and gutters with weed killer, instead of cutting or pulling the offending species, has made the situation worse. A plague of Brown-tailed Moths across the Channel Islands in 1997-99 resulted in widespread use of chemical insecticides in attempts to destroy their "tents" in which the eggs overwinter and which provide shelter for the developing caterpillars in the spring. This of course had the incidental effect of killing a lot of other butterfly and moth caterpillars and was not particularly successful in reducing the numbers of the moths, whose caterpillars have extremely irritant hairs if they are touched or accidentally brushed against. This sort of infestation tends, like plagues of locusts, to be cyclical and will probably subside shortly any way, but complaints about their effect on visitors, particularly in the dunes behind the best beaches resulted in a lot of work for the local hospital and panic in the States. Both types of spraying carry with them the additional hazard of the toxic chemicals used getting into the water table and thus into our drinking water.

Finally, generations of rubbish disposal at the "Impôt" two former small quarries on the coast near La Tchue worked well in Victorian times and up to 1939 when there was little domestic waste. Fields were ploughed regularly and the weeds turned in to help fertility. Garden waste was composted or burnt and thus recycled, to the great benefit of the land. There were few motor cars or other motorised machines, no fridges, washing machines, electric and gas cookers or TVs to need replacing and little in the way of builders waste, or nothing like milk cartons, beer cans or plastic containers to dispose of. It worked well and after burning, the remains were pushed over the cliff. Local fishermen gathered good lobsters and conger eels which made their homes in the occasional old lorry or bus pushed over into the deep water at the foot of the cliff.

Today's throwaway society has radically changed this. Everything from furniture, kitchen equipment, TVs and computers, tools, nails and screws, electric fittings, bedding and clothing, etc. etc., to virtually all foodstuffs, comes pre-packed in a variety of wooden, cardboard, and/or plastic bags, boxes or containers, all of which have to be disposed of. Fewer homes now burn solid fuel of any kind, so most of this ends up at the tip. From less than 25 cars in the island in 1930 there are now almost 2,500 and several end up at the Impôt every month. The population has increased by 50% in the same period. New owners of existing property have their kitchens and bathrooms remodelled and much of the old equipment and fittings is discarded. Double glazed units are being fitted to many homes and the old windows and doors thrown away. It is now illegal to feed pigs and chickens on household and hotel waste food and few people keep them anyway. Most waste, collected daily from business premises and domestic waste weekly from homes, was put into plastic sacks and together with old car and lorry tyres, burnt there, producing a pall of noxious black smoke, reputedly carcinogenic and, depending on the wind direction, more often than not blowing across parts of the island in the prevailing south-westerly winds. Builders take all their empty paint tins, old doors and window frames, kitchen units and plumbing materials, pipes and tanks and the plastic boxes and wrappings in which they were delivered there.

With a lack of many qualified service agents for TVs, radios, washing machines, etc. in Alderney, it is often cheaper and easier to buy a new one than to have the old one sent to Guernsey to be repaired and pay all the incidental (but now considerable) freight charges, as well as the repair costs.

No-one can really blame those who dispose of their waste this way, much of the packaging has no possible use for any other purpose and has gradually developed to make the presentation of anything more attractive to the potential purchaser and increase the profits of the manufacturers and distributors. EU regulations mean that cement can now only be sold in 25Kg bags virtually doubling the amount of waste paper produced by the old 1 cwt. bags and increasing the price accordingly. Gardens are mostly smaller than in the past and many have no suitable places to deal with the garden waste without upsetting the neighbours. The Alderney Wildlife Trust has organised a supply of cheap compost bins for domestic use, but many householders find it easier to take it to the Impôt rather than by composting or burning it at home. All garden maintenance contractors, have to do the same, here it is piled for compost and the heavy trunks and branches and other woody elements are turned into chips first.

The resulting atmospheric pollution and often unpleasant smell across the island, from the burning plastic and rubber, mixed with the other rubbish, has produced many complaints from residents about both the health hazard and the adverse effect on tourism. Although not part of the EU, the Channel Islands seem to feel obliged to accept many of its regulations imposed on the UK, some of them quite ridiculous, irrelevant and unnecessary, unsuitable, or beyond their financial means, for such small communities as Alderney and Sark.

The way of life of small rural communities is being adversely affected in many countries by these pointless bureaucratic regulations and considerable unnecessary expense being incurred by the taxpayer in employing the Inspectors required to police the regulations.

Burning at the Impôt is now only permitted when the wind is offshore, all the waste vehicles, domestic appliances, etc. are being crushed and exported and a recycling operation has been set up near the harbour. Paper, cardboard, tins, and plastic are separated by many of the inhabitants and put into a range of containers changed weekly, the cardboard is compacted and baled, and all this is exported and sold. The glass bottles are separated into bins, crushed and used as hard core and for making paving and other blocks on the island. Other domestic and shop refuse, disposable nappies, etc. are now sent to Guernsey for disposal, at great cost to Alderney.

The older systems for scrap metal and vehicle, rubbish and sewage disposal however presented both a health and an environmental challenge which is now being faced. The recent huge pile of scrap cars, trucks, batteries, and domestic equipment has been sent by sea to UK for recycling. This has been an occasional event in the last 3-4 years but will be better organised and more regular in future. For the last couple of years a bottle bank and a container for aluminium drinks cans has been set up near the harbour and cleared frequently. Two shiploads of scrap were eventually exported in July 2000, but within a month about 30 scrap cars and small trucks had accumulated at the Impôt and were set on fire on Saturday evening 19th August, by an unknown arsonist, resulting in considerable work and trouble for the volunteer fire brigade, who had to use breathing apparatus to tackle the blaze with the use of 1,000 gallons of foam, .........Figure 80. Scrap cars being piled for export, 15.5.2000................ at great expense to the community, to extinguish the fire. Black smoke ascending from the burning cars was visible all over the island and from Guernsey, 20 miles away. Fortunately the wind was light and only a small area of the cliffs was set alight, taking about 1,000 gallons of water to control and damp down the surrounding area.

The older systems for scrap metal and vehicle, rubbish and sewage disposal however presented both a health and an environmental challenge which is now being faced. The recent huge pile of scrap cars, trucks, batteries, and domestic equipment has been sent by sea to UK for recycling. This has been an occasional event in the last 3-4 years but will be better organised and more regular in future. For the last couple of years a bottle bank and a container for aluminium drinks cans has been set up near the harbour and cleared frequently. Two shiploads of scrap were eventually exported in July 2000, but within a month about 30 scrap cars and small trucks had accumulated at the Impôt and were set on fire on Saturday evening 19th August, by an unknown arsonist, resulting in considerable work and trouble for the volunteer fire brigade, who had to use breathing apparatus to tackle the blaze with the use of 1,000 gallons of foam, .........Figure 80. Scrap cars being piled for export, 15.5.2000................ at great expense to the community, to extinguish the fire. Black smoke ascending from the burning cars was visible all over the island and from Guernsey, 20 miles away. Fortunately the wind was light and only a small area of the cliffs was set alight, taking about 1,000 gallons of water to control and damp down the surrounding area.

...

A Salvation Army container was provided for surplus clothing, bedding, etc for a few years, it was well used but has now been withdrawn owing to difficulty in disposing of the large amount of clothing collected. Active steps were being taken in 1999-2002 to obtain or build a suitable incineration plant for the domestic rubbish. This would have reduced the wind blown plastic and other rubbish seen along the cliffs near La Tchue and floating debris carried by sea, mainly round to Longis Bay, the second largest and most popular beach in the island, but has been banned by Guernsey who are themselves about to build a new incineration plant.

Part of the town foul-water drainage system has been treated in the filter beds at Longis Bay for at least 20 years. More properties have recently been linked to this system, but the greatest number of properties either have drains linked to the untreated sewage outfall at Crabby Bay, which is far too near the shore for comfort, or have their cess pits regularly emptied by the States with the contents then being disposed of through this same outfall. This too is being examined, but an effective remedy will prove vastly expensive and the direction and falls of the various existing sewers will still not allow many properties to be connected to them unless additional pumping stations are built.

Almost in spite of these man-made problems, the area along the south cliffs still holds many interesting plant and animal species. The cliff path westward along the coast from the top of Essex Hill can be a delight when the Impôt is not burning. Bare patches on the cliffs hold a wealth of small plants including the Sand Crocus, Autumn Squill and Shepherd's Cress. On Essex Hill the largest remaining concentration of Primroses flourishes, with a mass of Common Dog Violets scattered through the grass and patches of Honesty, Variegated Catchfly, Great Quaking-grass; Bluebells, the native, the Spanish and hybrids between them in

some profusion. Another tiny colony of Sand Quillwort manages to survive in a small hollow and, in a square stone tank, partly water filled throughout the year, the island's only stand of Greater Reedmace Typha latifolia (Figure 81, on left, now officially called "Bulrush", a name formerly reserved for a different plant), is to be found. In this species there is no gap between the male and female flowers forming the brown mace head at the top of the flowering stems. Probably originating as either the cellar of, or a water storage tank for, the Coast Guard Lookout house built here in 1906, used by the Germans during the war as a lookout for their antiaircraft batteries situated on top of the hill here, but demoli

some profusion. Another tiny colony of Sand Quillwort manages to survive in a small hollow and, in a square stone tank, partly water filled throughout the year, the island's only stand of Greater Reedmace Typha latifolia (Figure 81, on left, now officially called "Bulrush", a name formerly reserved for a different plant), is to be found. In this species there is no gap between the male and female flowers forming the brown mace head at the top of the flowering stems. Probably originating as either the cellar of, or a water storage tank for, the Coast Guard Lookout house built here in 1906, used by the Germans during the war as a lookout for their antiaircraft batteries situated on top of the hill here, but demoli

shed soon afterwards, this tank a

shed soon afterwards, this tank a

lso holds a few plants of the Fringed Water-lily Nymphoides peltata (Figure 82, above), and a considerable amount of the pernicious alien New Zealand Pigmy-weed Crassula helmsii (Figure 83, on left), all probably introduced originally. The latter having since spread into the ponds at Longis and Mannez and other places.

lso holds a few plants of the Fringed Water-lily Nymphoides peltata (Figure 82, above), and a considerable amount of the pernicious alien New Zealand Pigmy-weed Crassula helmsii (Figure 83, on left), all probably introduced originally. The latter having since spread into the ponds at Longis and Mannez and other places.

Beyond the Impôt the cliff path crosses the road leading to it from Longis Road. On the right here, beyond the large field are the remains of an old brick kiln. The level area close by this was composed of wind blown loess from many millennia ago and was used to make bricks, probably in the late 18th/early 19th centuries. close to the brick kiln lies a large Neolithic stone circle. The origins of this and any possible past archaeological work done here are somewhat obscure.

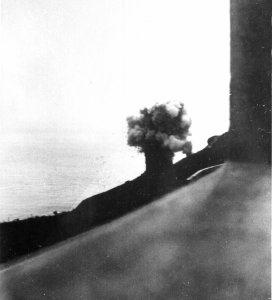

Keeping to the cliff path however, we descend a steep slope and, to the left of this down an even steeper track, there is the first of the remaining abreuvoirs publiques, the cattle watering troughs, kept filled by a small spring nearby. A good view of the Hanging Rocks to the east is gained from here. These geological freaks of (presumably) harder sandstone than that which had surrounded them, were somewhat modified during the Second World War, when the Germans blew the top off the larger of the two. A photograph of this actually happening, taken by a German soldier from Fort Essex has survived.

Both photos here by a German Soldier, Asbeck, August or September 1941.

.Fig. 84. Shelling the Hanging Rocks.......... Fig. 85. The Coast Guard lookout during the war.

Large tracts of gorse clothe the cliffs beyond this track with a number of Alderney's not very common wild roses among them. This is ideal country for the Dartford Warbler and you may see them anywhere along the next mile or so. A few areas are still lightly covered with scrub and several small, rare in Alderney in not elsewhere may be found in the barer patches. Chief amongst these is the Annual Knawel Scleranthus annuus, only previously recorded in 1908 and 1951, until it was found by the author along here, in some quantity over a few square metres, in 1996 and yearly since. It seems most likely that it had been overlooked in the interim. In the short trodden turf of the cliff path here, in early May look for several minute members of the pea family. The pink and white flowered Bird's-foot Ornithopus perpusillus is frequent, with the very much rarer Orange Bird's-foot O. pinnatus seen in small patches. Two of the Bird's-foot-trefoils, Hairy Lotus subbiflorus and Slender L. angustissimus may be found by the careful observer. Masses of several different Vetches, Hairy Tare, Vicia hirsuta, Common and Narrow-leaved Vetch V. sativa and V. sativa subsp. nigra, and Lucerne Medicago sativa appear along the edges of the scrub and on the wall bounding the Grande Blaye.

This path is one of the places you might encounter the Slowworm as well.

Just below the path on the seaward side you will notice a white navigation cone part way down the cliff, above Bluestone Bay. Placed here as a mark for ships using the Cachalière Pier to load stone after the diorite quarry was opened, about the turn of the 20th century, it is the end of this region of our survey and also marks the end of the sandstone overlay along the south cliffs. Just below the cone, on the almost bare sandstone slides is the habitat of another of our endangered species rare plants, Flax-leaved St. John's-wort Hypericum linariifolium.

Beware; do not try to get down to this site from here, it is far too dangerous.

The best approach to the beach is down a very narrow winding track from Les Becquets headland about 50m east of this spot. This is also somewhat hazardous, but with great care you can reach the beach safely, if the tide is down. This beach is composed of a thick layer of blue, water-worn, diorite pebbles, over the sandstone, a legacy of the stone crushing activity from the quarry just beyond the headland between about 1890 and 1924.

Figure 86. Flax-leaved St. John's-wort

At low tide the offshore stack L'Etac de la Quoire, is connected by a natural causeway to the end of the beach and is the breeding place of many seabirds. The headland here marks the first exposed section of the central diorite, (see the geological map (Figure 1), on page 2), which was the reason for the start of the quarrying industry on this section of the coast. It will be dealt with, in the next chapter.

......

Figure 87. L'Étac de la Quoire from Bluestone beach

.